1893

Under the auspices of The Mizpah Circle, The Industrial Home for the Blind officially opens its doors at its original location of 96 Lexington Avenue in Brooklyn.

1894

The Industrial Home for the Blind provided a home to 17 men who are blind, 10 of whom are employed producing cane seats, hair mattresses and brooms. In the organization’s very first annual report, Mr. Eben Porter Morford states, “The growth of the institution has ever since been a steady healthful nature and there has been nothing spasmodical in its advancement.”

1895

The Industrial Home for the Blind is officially incorporated under the laws of the state of New York. The agency’s first mission was, “to teach a trade to the blind so that they may earn their own living and become self-supporting.”

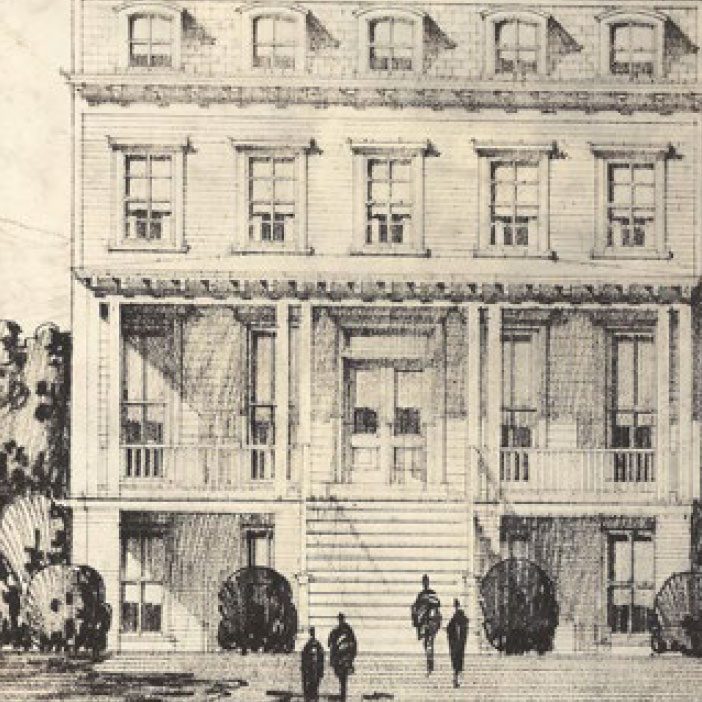

1899

The Industrial Home for the Blind moves to a new residence and factory building on 512-516-520 Gates Avenue in Brooklyn. Eventually, 55 men are employed at this location, 16 of whom reside at the facility.

1906

Mr. Morford participates in a study of the needs of individuals who are blind and reside in the state of New York. This study helps to inaugurate The New York State Commission for the Blind, an agency that today remains a longtime important partner of the agency.

1917

The Industrial Home for the Blind creates rehabilitation services for individuals who are DeafBlind. Mr. Morford hires a young Peter J. Salmon, a man who would later be instrumental in significantly expanding these programs for DeafBlind people.

1920

The Industrial Home for the Blind hires its first professionally trained social workers and subsequently begins a social services department to aid people who are blind.

1928

The Industrial Home for the Blind hits a milestone by serving over 600 individuals who are blind or DeafBlind.

1929

The agency begins to provide vocational counseling and job placement services.

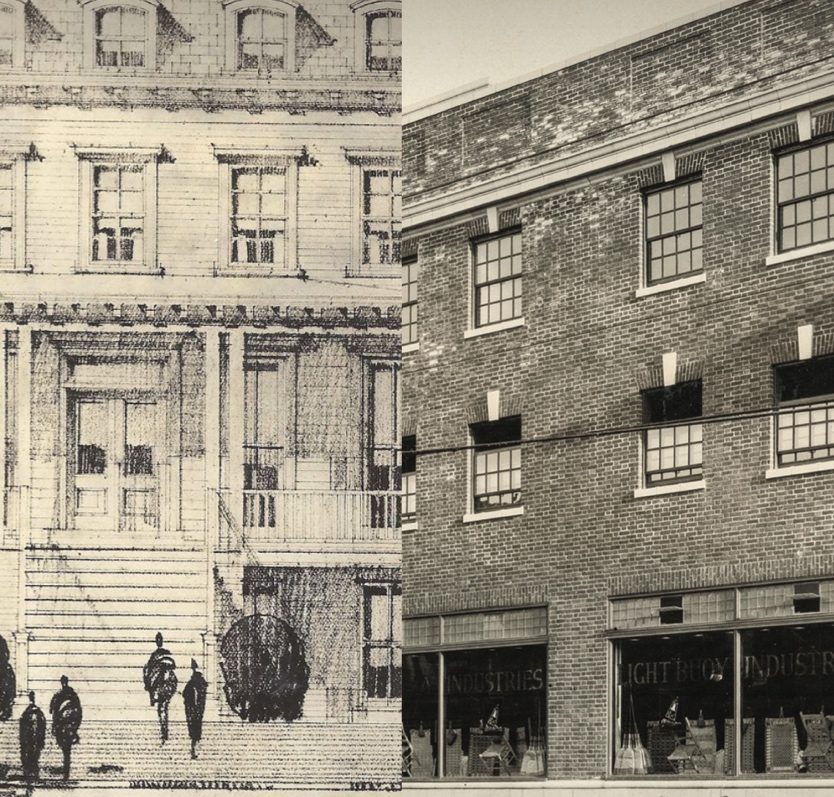

1941

The Industrial Home for the Blind moves to a new location at 1000 Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn.

1942

The events of World War II enable the public to realize how people who are blind can make significant contributions to the economy. The high-quality work performed by employees of The Industrial Home for the Blind is recognized by the military, as the agency is awarded the Army-Navy “E” Pennant for exceptional performance, high production of goods and low absenteeism.

1943

Helen Keller visits The Industrial Home for the Blind and declares, “True celebration will be the continued progress of the Brooklyn Industrial Home. When it has opened all doors for the blind to health, happiness and integration into normal society, its mission of restoring love and constructive faith will be fulfilled.”

1945

Thanks to the personal commitment of Dr. Peter J. Salmon, a formal program for people who are DeafBlind is created.

1946

The agency opens recreational day centers for older adults who are blind (discontinued in 2012).

1947

The Industrial Home for the Blind establishes the nation’s first comprehensive rehabilitation center for individuals who are blind or have low vision, signaling an overall organizational shift from the original single focus of employment to a more comprehensive program of education and rehabilitation.

1949

The Industrial Home purchases the Burwood Home in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, a residential facility for elderly individuals who are blind or DeafBlind (sold in 1985).

1951

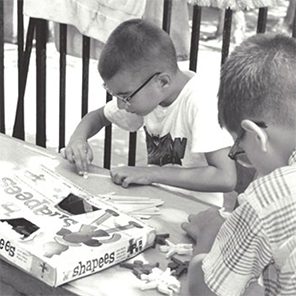

The Industrial Home for the Blind advocates for the registration of children who are blind in mainstream Long Island public schools.

1952

The agency creates a nursery for infants and children with low vision. Additionally, The Industrial Home for the Blind employs New York’s first itinerant teacher for students who are blind on Long Island.

1953

The organization opens a Low Vision Center, the first of its kind, in Brooklyn. Its goal is to provide diagnostic services, specialized low vision aids, and glasses for individuals with functional residual vision. A day camp that provides social, physical and recreational activities for children and youth who are visually impaired also begins in Long Island (officially renamed Camp Helen Keller in 1998). The Industrial Home for the Blind opens The Braille Library in Hempstead, New York (discontinued in 2012).

1956

The Industrial Home for the Blind and The United States Office of Vocational Rehabilitation collaborate on a two-year study to determine the needs of the DeafBlind population. The study concludes that individuals who are DeafBlind would best be served on a regional basis, thus establishing the federally-funded Anne Sullivan Macy Service.

1958

The agency’s first speech and hearing service for people who are blind is formed.

1967

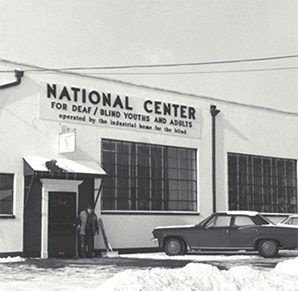

As a result of the longstanding commitment to the DeafBlind population of Dr. Peter J. Salmon and others, The Helen Keller National Center for DeafBlind Youths and Adults is established by a unanimous act of Congress. The Industrial Home for the Blind establishes the Preschool Vision Screening Program (discontinued in 2012).

1969

The Industrial Home for the Blind is formally designated to operate The Helen Keller National Center, and temporary training facilities are set up in New Hyde Park, New York. The New England regional office opens in Boston, Massachusetts (relocated to Watertown in 2011).

1970

The Helen Keller National Center opens its Southwest regional office in San Francisco, California and its Southeast regional office in Atlanta, Georgia.

1971

The Industrial Home for the Blind expands its nursery for infants and children who are blind, made possible through a partnership with New York City Board of Education’s Rubella Program. The Helen Keller National Center opens its North Central regional office in Chicago.

1973

he East Central regional office in Pennsylvania is established.

1974

The South Central regional office for The Helen Keller National Center opens in Dallas, Texas (relocated to Austin in 2012).

1976

The headquarters of The Helen Keller National Center for DeafBlind Youths and Adults officially opens at its permanent location of 141 Middle Neck Road in Sands Point, New York.

1977

The Helen Keller National Center establishes its Northwest regional office in Seattle, Washington and its Rocky Mountain regional office in Denver, Colorado.

1978

The Great Plains office opens in Shawnee Mission, Kansas.

1979

The Industrial Home for the Blind opens a Rehabilitation Center in Hempstead, New York.

1983

The organization obtains a multi-year contract with The New York State Office for People With Developmental Disabilities. As a result, The Day Habilitation Program for individuals who are blind and developmentally disabled begins at the agency’s Hempstead office.

1984

President Ronald Reagan signs a proclamation officially declaring the last week of June every year as Helen Keller DeafBlind Awareness Week.

1985

The Industrial Home for the Blind changes its name to Helen Keller Services for the Blind in memory of longtime friend and supporter Helen Keller.

1988

The nursery for infants and young children who are visually impaired with additional disabilities becomes The Children’s Learning Center in Brooklyn. This is made possible thanks to newly established partnerships with The New York State Education Department and the New York City Department of Education. Additionally, the agency’s first Assistive Technology Center launches in Hempstead.

1989

Helen Keller Services for the Blind opens a Rehabilitation Center in Huntington, New York. The Helen Keller National Center starts its Older Adults Program.

1990

Helen Keller Services for the Blind creates the Annual Golf Classic, an event designed to raise funds for various programs and services. The agency opens a second Assistive Technology Center in Brooklyn.

1994

Helen’s Walk, a public event designed to engage members of the community and individuals who are DeafBlind, begins in Sands Point (renamed Helen’s Run/Walk in 2013).

1999

Helen Keller Services for the Blind opens an additional Low Vision Center and Assistive Technology Center at its location in Huntington.

2002

Helen Keller Services for the Blind creates the Individualized Residential Alternative in North Bellmore, New York, a residence for several individuals who were participating in the Day Habilitation services.

2003

The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust Conference Center is completed at The Helen Keller National Center. A woodshop, conference center, board room and 10 offices are added to the headquarters as a result

2004

The Parent and Early Education Resource Center opens in Brooklyn to provide educational and support services for parents of children who are blind and/or experience multiple disabilities.

2006

The Helen Keller National Center begins collaborating with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on a Rubella biomarker study.

2008

The Destiny Home for individuals who are DeafBlind with intellectual disabilities is established in Port Washington, New York.

2009

Northern Illinois University collaborates with The Helen Keller National Center to offer a Certificate in DeafBlind Rehabilitation, which includes an online program and an eight-day practicum at the Sands Point facility.

2010

A Support Service Provider program is established at The Helen Keller National Center’s location in San Diego, California.

2011

The Children’s Learning Center celebrates the matriculation of 19 preschoolers, the largest graduating class in the preschool’s history. The Helen Keller National Center begins collaboration with the National Institutes of Health on a genetic study of Usher syndrome.

2013

Camp Helen Keller celebrates its 60th anniversary.

2014

Sands Point Garden Club celebrates the complete renovation of HKNC’s Sensory Garden for students with dedications in memory of longtime Long Island advocates. HKNC establishes the Dr. Robert J. Smithdas Award in memory of the Center’s co-founder and former director of community education, who passed away earlier in the year at age 89. The inaugural award presentation coincides with Helen Keller DeafBlind Awareness Week, and award recipients include Congressmen Kevin Yoder (R-KS), Mark Takano (D-CA) and Steve Israel (D-NY).

2015

A rebranding initiative is launched, introducing a new name and new logos to better identify the organization and its two divisions. The new name, Helen Keller Services (HKS), is now used to identify the entire organization and clarify the relationship between its two divisions: Helen Keller Services for the Blind (HKSB) and the Helen Keller National Center for DeafBlind Youths and Adults (HKNC). HKSB opens a new Suffolk County location in Ronkonkoma. Made possible through generous funding obtained by State Senator Philip Boyle (4th Senate District), the new office is larger and more centrally located for clients. The 3900-square-foot facility includes a low vision eye service, rehabilitation services and an assistive technology center.

2018

HKS moves to its new headquarters at 180 Livingston Street.

2021

Virtual classes continue due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Terminology changes from “deaf-blind” to “DeafBlind”. HKNC field expansion and HKSB CLC expansion. Susan Ruzenski is named Chief Executive Officer of HKS. Deborah Harlin is appointed HKNC’s Executive Director. The Technology, Research, and Innovation Center is created. HKS holds the first annual AccessAbility Awards. HKS’ partnership with the first film to cast a DeafBlind actor “Feeling Through” is nominated in the 93rd Oscar Ceremony.

2022

HKS joined as an affiliate with NIB with NY State Preferred Source Program for jobs creation in website accessibility testing. HKS launches new website as a national resource with the communities we work with. HKNC continues to expand services both locally and statewide. HKS obtains its first CARF accreditation. HKS held inaugural Tech Blitz for vendors, trainers, and community members.